Central and Eastern Europe countries, the former “Eastern Bloc” of Soviet satellites, have completed almost 35 years of post-Communist transition, an entire generation. By now, the countries in the region are doing much better than under Communism. By and large, these countries are all “high-Income” countries, based on the World Bank definition (Gross National Income per capita greater than US$13,000 ). Most of these countries have become members of the European Union and their economies are increasingly integrated in Europe.

Capital markets in the region have been established for a while now. Have they become a major financing and investment engine for their economies? We believe a lot remains to be done to get there and propose some practical steps.

The Central and Eastern European region is shown on the map below. We include the former Eastern Bloc , but exclude (for the time being), countries which used to be part of the Soviet Union proper – Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova. The Baltics (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) are also a special case since they used to be Soviet and in many ways are closer to the Nordic region.

By and large, the Central and Eastern European region is quite fragmented: 17 countries and multiple languages, currencies, legal frameworks and overall traditions.

Overall the region’s population is 126.5 million, quite sizable.

The table below ranks the countries by population size, from the largest, Poland, to the smallest, Montenegro. Apart from one large country, Poland and one medium-sized country, Romania, the remaining countries are fairly small or very small.

Their GDP/Capita ranges from almost-Western European standards (Czechia) to low levels in countries such as Albania or Kosovo. The average GDP/capita for the region as a whole is $37,200 , considered clearly high-income by the World Bank.

|

Country |

Population |

GDP |

GDP/cap |

Exchange |

Market |

MktCap/GDP |

||||

|

(PPP) |

(PPP) |

Cap |

||||||||

|

Million$ |

Billion$ |

$0 |

Billion Euro |

% |

||||||

|

Poland |

38 |

1599 |

42.1 |

Warsaw |

138 |

9% |

||||

|

Romania |

18.5 |

731 |

39.5 |

Bucharest |

27 |

4% |

||||

|

Czechia |

11 |

515 |

46.8 |

Prague |

27 |

5% |

||||

|

Hungary |

9.7 |

410 |

42.3 |

Budapest |

25 |

6% |

||||

|

Greece |

10.5 |

388 |

37.0 |

Athens |

55 |

14% |

||||

|

Slovakia |

5.4 |

211 |

39.1 |

Bratislava |

2 |

1% |

||||

|

Bulgaria |

6.8 |

198 |

29.1 |

Sofia |

6 |

3% |

||||

|

Serbia |

6.7 |

165 |

24.6 |

Belgrade |

5 |

3% |

||||

|

Croatia |

4.2 |

150 |

35.7 |

Zagreb |

18 |

12% |

||||

|

Slovenia |

2.1 |

105 |

50.0 |

Ljubljana |

10 |

10% |

||||

|

Bosnia |

3.8 |

62 |

16.3 |

Sarajevo |

3 |

5% |

||||

|

Albania |

3.1 |

51 |

16.5 |

Tirana |

||||||

|

Cyprus |

1.3 |

45 |

34.6 |

Nicosia |

6 |

13% |

||||

|

N.Macedonia |

2.1 |

41 |

19.5 |

Skopje |

2.5 |

6% |

||||

|

Moldova |

3.3 |

41 |

12.4 |

Chisinau |

||||||

|

Kosovo |

2 |

25 |

12.5 |

Pristina |

||||||

|

Montenegro |

0.6 |

16 |

26.7 |

Montenegro |

3 |

19% |

||||

|

Total |

126.5 |

4712 |

37.2 |

324.5 |

7% |

|||||

|

Memo: |

||||||||||

|

Austria |

8.9 |

599 |

67.3 |

Wien |

116 |

19% |

||||

|

Turkey |

83 |

3320 |

40.0 |

Istanbul |

293 |

9% |

||||

Small Markets, Little Growth

The capital markets of these countries remain very small relative to the size of the underlying economies. The classical metric, the ratio of Market Capitalization / GDP, averages 7%, for the region as a whole. This ratio is very low. By contrast, in developed economies, with well-developed capital markets Market Capitalization/ GDP tends to be in the 50% -150% (and more) range.

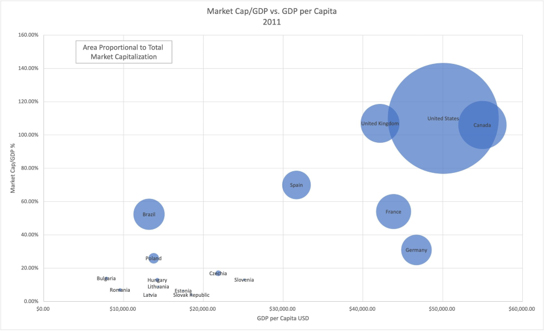

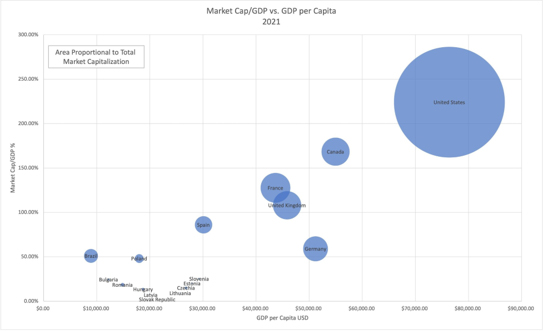

The two charts below illustrate the relationship of Market Capitalization / GDP as a function of GDP/ Capita at two points in time, 2011 and 2021, a decade apart. The size of the circles is proportional to the absolute market capitalization of each country

More developed countries tend to have more important capital markets relative to the size of underlying economies. Note that while Market Capitalization to GDP has increased significantly during the 2011-2021 decade in the developed, advanced markets, it has remained at about the same low levels, for Central and Eastern European markets..

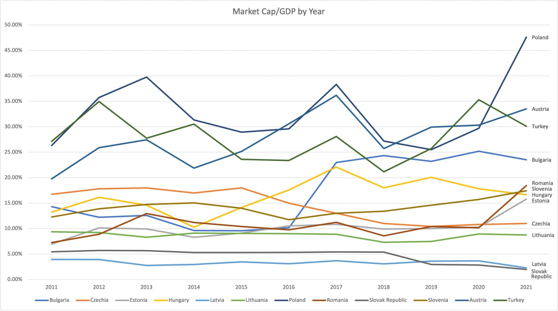

The 10-year time series data for the same indicator, also shows that most Central and Eastern European markets have not progressed very much during the 2011-2021 decade. The exception is , of course, Poland, which was upgraded to developed market rating . Romania has also improved in the last few years and was rated emerging market by one agency. Austria and Turkey, two older markets close to Central and Eastern Europe are added for reference.

More granular indicators of activity of Central and Eastern Europe markets also show a fairly stagnant situation.

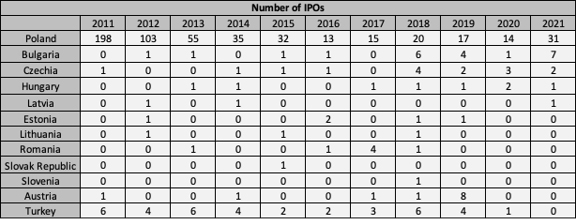

Apart from Poland, IPO activity has been very low….

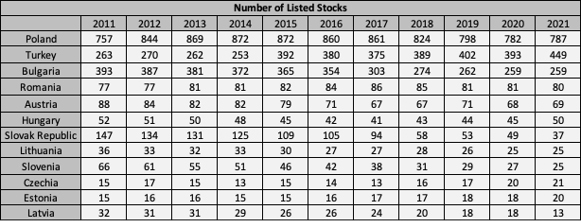

Not surprisingly, the number of stocks listed on Central and Eastern Europe has also remained stagnant over the same decade, 2011-2021

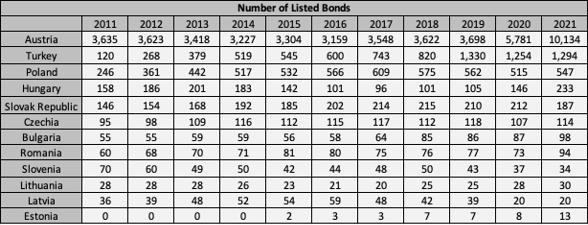

Similar story for the number of listed bonds (although in all fairness there has been a moderate spurt of bond activity during the latter part of the decade, due presumably to the very low interest rate environment)….

To sum up, all of the above indicators suggest that the Central and Eastern European capital markets have mostly stagnated during the decade from 2011 to 2021.

Lack of Liquidity

These markets have also been hampered by a chronic lack of liquidity.

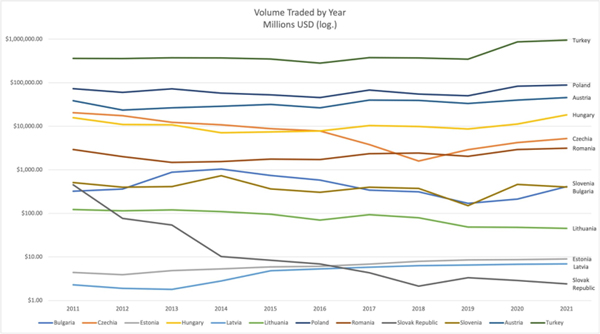

The chart below shows the evolution of annual volume traded in Central and Eastern Europe markets over the 2011-2021 decade. Clearly volumes traded have not grown much during this period.

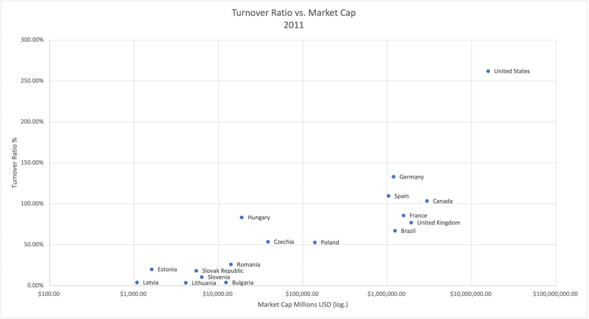

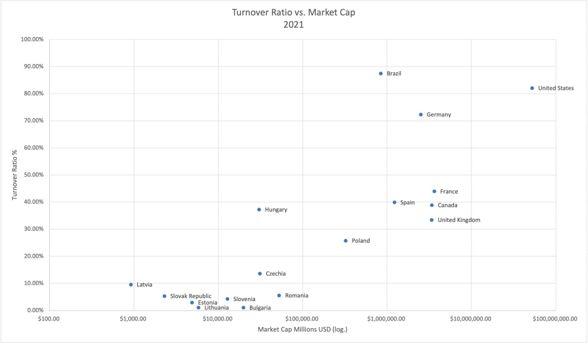

A more interesting market liquidity metric is the Turnover Ratio, defined as Annual Volume Traded/ Market Capitalization.

Larger markets , with greater market capitalization, usually are characterized by higher turnover ratios, reflecting a larger, more diverse number of players active in the market.

The charts below show this relationship at two points in time, a decade apart: 2011 and 2021. Note that the x-axis of the charts is logarithmic. Empirically, every time Market Capitalization increases by a factor of 10, liquidity, measured by the Turnover Ratio, increases by roughly 50%

Note that while turnover ratios in the advanced developed markets have varied (they were higher in 2011 than in 2021, reflecting different market conditions), they have remained chronically low in Central and Eastern Europe.

Why are Central and Eastern European markets relatively illiquid? What are the consequences of this lack of liquidity?

These markets are caught in a “chicken-and-egg” story : small market size – lack of liquidity – few investors - few issuers

In any market, liquidity is a function of how many traders or players there are and how active they are. The challenge in Central and Eastern Europe is that there are, for the time being, relatively few active investors. Let us review various categories of actual and potential investors.

Local Institutional investors.

Most of these countries have already established funded pension funds some time ago. Pension funds automatically collect contributions from the people enrolled in them and are therefore tremendous aggregators of “assets-under-management”. These assets must be invested in order to generate the returns necessary to pay pensions. In some countries, like Poland and Romania, the pension funds have already reached a respectable size. However, from the liquidity standpoint there is a problem: pension funds are typically “buy-and-hold” investors. They are not very active traders and do not generate much liquidity in their markets.

Local Retail Investors

Retail investors can be fairly active traders. In the well-developed equity markets, such as the US, Canada, UK, Australia and many other countries influenced by the “Anglo-Saxon model”, the Asian markets and markets such as Brazil, retail investors play a critical role and generate very significant liquidity.

In Central and Eastern Europe, retail investors are very conservative, and tend to place their savings in bank deposits and real estate. There are younger, more aggressive investors who are interested in stocks, however their first instinct is to invest in American stocks, especially NASDAQ and the fashionable “Magnificent 7”

Hedge Funds, Futures Funds and Professional Active investors

This category of investors contribute a high amount of liquidity to the markets in which they trade. These are usually highly active traders. Their trading strategies naturally involve multiple positions and arbitrage. In markets where derivatives are available, such traders will engage in strategies across cash and derivatives markets. However, such professional traders need a minimum threshold of liquidity in the underlying markets in order to implement their strategies. They tend to stay away from markets that do not meet such liquidity criteria. Not surprisingly, such professional traders are very scarce or inexistent in Central and Eastern Europe.

Foreign Investors

Foreign global investors could also be a major source of liquidity. However, these tend to be large funds (especially the large passive investors )and they need to invest large amounts in large companies. It is not easy to find enough suitable targets in the smallish Central and Eastern European markets. Global investors also need a minimum threshold of liquidity to be able to trade in or out of the markets without excessive price impact. Central and Eastern European markets do not offer the required liquidity.

Overall, Central and Eastern European capital markets (except Poland ) suffer from a lack of “critical mass”. They do not have enough active investors and cannot offer sufficient liquidity.

Issuers

Whenever a company considers raising capital and contemplates an IPO, or a secondary offering or a bond issue, the key considerations are whether there are enough potential investors and whether there will be liquidity in the market. Even if a new issue gets placed , lack of liquidity in the aftermarket is a major problem, since it can affect prices and sour the initial investors. Lack of liquidity in the market is therefore a negative factor for issuers and will discourage them from using the capital markets.

Bottom line: In Central and Eastern Europe, capital markets remain subcritical and unable to become major financing vehicles for the local economies. The local economies remain dependent on traditional bank financing.

Strengthening the Central and Eastern European Capital Markets: What can be done?

What can be done to strengthen Central and Eastern European capital markets?

It is useful to examine actual cases of regions with fragmented markets, similar to Central and Eastern Europe, and see how they evolved.

Nordics: Consolidation via Mergers and Acquisitions; Many common underlying links

The OM Nordic exchanges (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) are the result of a series of mergers among the Scandinavians initially, followed by the Baltics. The Swedish exchange, OM, was in fact the first major exchange to privatize in the late 1980s. Once privatized, OM start EDseeking acquisition opportunities, in the Nordic region, as early as the 1990s. NASDAQ then acquired OM in a bold move to build a global exchange and completed the series of Nordic acquisitions. The consolidation process was fairly natural, since Scandinavian countries have many historic links, business links, language and cultural similarities and the Baltics have their shared history under the Soviets as well as many traditional links to Scandinavia.

ASEAN Link: Federation of Exchanges: coalition of dynamic markets, but different languages and legal systems

ASEAN Link is the federation of South East Asian exchanges ( Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam and Philippines), which started around 2015. These countries are all very dynamic “Asian Tigers” with booming economies and buoyant stock markets. However, they have very different languages and cultures. It was pretty clear from the beginning that mergers were unlikely to happen, since each country wishes to have their own exchange. As a result, ASEAN Link took several interesting initiatives: establishing a South East Asian “asset class” by creating common indexes, uniform databases and analytics for the region and implementing an order routing network ( initially among 3 of the countries Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia). Order routing was meant to enable a broker in one country to execute orders directly in another country and thus encourage regional investment across national borders. After several years, the order routing network proved to add little value. The regional indexes and the analytics however were a success and helped increase global investors’ awareness and interest in the South East Asian region.

MILA (Mercado Integrado Latino-Americano): Federation of Smaller Latin American Exchanges

MILA, started around 2016, was the federation of the Chilean, Peruvian and Colombian exchanges in South America. The South American region includes a giant exchange, Brazil and a somewhat smaller giant, Mexico. The smaller markets wanted to get together and avoid being dominated by the two giants. Initially, MILA followed the ASEAN model ( common indexes and analytics, an order routing network ). Just like in Asia, the order routing network failed to generate any significant incremental volume. After several years, the exchanges of Chile, Peru and Colombia decided to merge. These markets share the same language, Spanish and similar legal and institutional frameworks.

These three experiences suggest that, where the merger and acquisition route is open, this is what eventually happens and consolidation of markets is the natural endgame. Federations are more challenging.

What about Central and Eastern Europe?

In a sense, Central and Eastern Europe can claim to have “been there, done that”.

Vienna Stock Exchange did start a process of consolidation by acquiring equity stakes in the Budapest, Prague and Ljubljana exchanges and implementing a common technology platform across these markets. But there was no full consolidation, and, in the end, Vienna Stock Exchange stopped pursuing it.

In the Balkan region, there was a project, SEE, to create an order routing network among several bourses in the former Yugoslavia and the Bulgarian exchange. Just like the other order routing projects we reviewed, this one failed to create any incremental benefits and was practically abandoned.

So, what can be done?

The countries in Central and Eastern Europe are very different from each other, in terms of language, legal and institutional frameworks.

We do not, at this time, see any appetite for exchange mergers in the region. However, the region needs to energize its capital markets and adopt some common initiatives

What makes sense is to adopt some of the lessons of ASEAN and build upon them. The following is a suggested menu of ideas:

- Create a Regional Community of Exchanges – this should be a forum for the capital markets in the region.

- Promote a “Central and Eastern Europe Asset Class”– launch an outreach effort aimed at regional and global investors, via events and communication campaigns. Encourage investors from the region to seek opportunities in Central and Eastern Europe

- Create a common media platform: distribute regional news and insights from issuers, investors, intermediaries to stimulate interest in investing in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Create a family of regional indexes : for the overall region and for key sectors (e.g. banks, telecoms, energy, transport, retailing…). These indexes should be produced by an independent index provider.

- Create a common « analytics » web site: prices, analytics, broker research and independent quantitative research

- Create remote memberships allowing brokers to trade on affiliated exchanges (the EU passport already allows that for EU members, but remote memberships are needed for others)

- Develop shared technology platforms.

- Develop ETF products – for the region, with local listings as well as on major global markets (New York, London e.g.). This is fairly challenging since the underlying markets still lack the liquidity required to support US, UK and EU listed ETFs.

- Encourage the buy-side to develop families of regional-focused funds.

- Encourage the emergence of financial advisors to stimulate retail investment: such advisors can be professionals with suitable licensing as well as robo-advisor platforms.

The above initiatives will clearly take time and effort for the bourses and the brokers in the region. But the return on such an effort is clear. The region is at a very low starting point and should aim high.